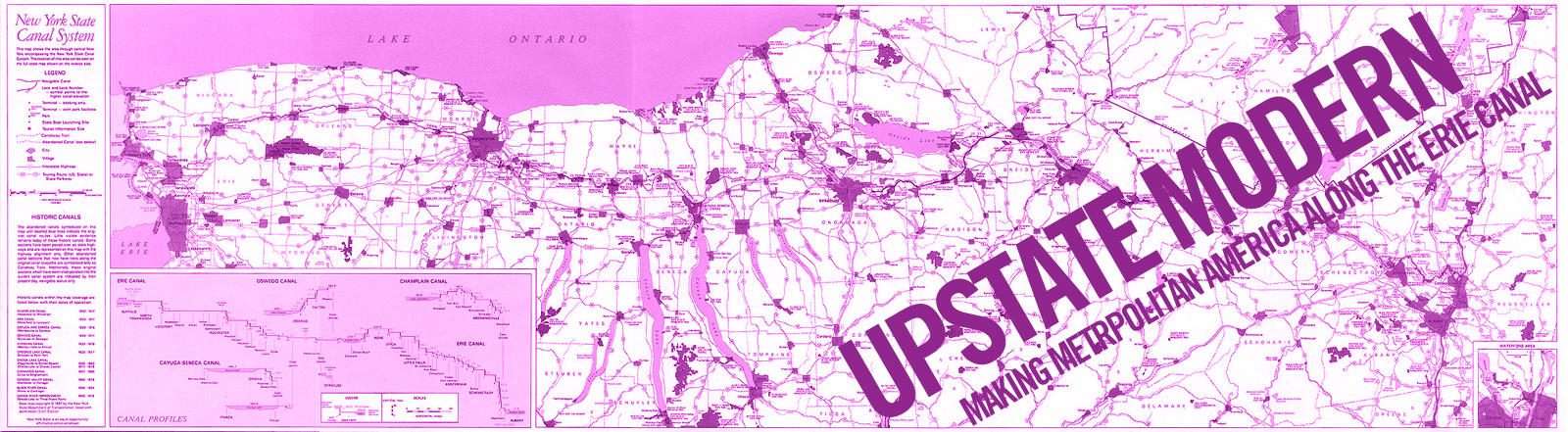

Upstate Modern MAKING METROPOLITAN AMERICA ALONG THE ERIE CANAL

Upstate Modern is a series of courses and public programs at Syracuse University examining the urban history of Upstate New York through transdisciplinary research that draws on archives, buildings, landscapes, and communities.

Rome Resurrected

By Eric LeBlanc.

Rome rebuilt 18th century Fort Stanwix as part of an urban renewal scheme, but the project failed to stimulate a post-industrial economy based on tourism.

A demonstration of a new environmental ideal for the American home, this photograph repeats tropes of man and nature; what-is-inside and what-is-outside; machine and garden

Fort Stanwix National Monument stands today as a unique example of urban renewal in an Upstate New York town whose economy was in a clear state of flux for much of the 20th century. In the years following World War II, Rome NY suffered from high unemployment, dilapidated city blocks, and an economically failing manufacturing industry. Rome’s central downtown district, the site upon which the original Fort Stanwix had stood in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century, was once characterized by stately mansions and architecturally elegant buildings. A housing shortage quickly called for the gutting and restructuring of these buildings into derelict apartments, stripping them of their former charm. In the aftermath of the First World War, the once thriving cheese industry and other agricultural industries (including cotton and wood) declined quickly. The railroads and canals that passed through Rome and contributed to its once thriving economy would quickly become overshadowed by cars, trucks, and highways that bypassed the city. Even Rome’s renowned copper industry for which its nickname derives began to suffer with the shift from durable goods (tools, guns, locomotive parts) to a focus on electronics parts, and the rise of plastics, stainless steel, and aluminum. Griffiss Air Force Base, which for years shielded Rome from economic disaster prior to the 1960s, finally faced its own disaster as budget cutters removed Rome Air Materiel Area. The removal represented a colossal loss of about twenty-seven hundred jobs for Rome (Zenzen 37).

Decades of neglect, urban decay, and deteriorating industrial vestiges would take its toll. In 1958, Rome became invested in urban renewal, which was the federal government’s response to post-WWII concerns of inadequate housing in deteriorating cities. Through Congress’s 1949 Housing Act and a number of amendments to the bill leading up to 1959, Rome’s southern central business district would be the target of a sweeping demolition project that removed twenty-four acres of old buildings, warehouses, junkyards, and residences. The 1967 Master Plan implemented new retail enterprises including a shopping center, restaurants, a motel, and a complete reconstruction of Fort Stanwix on its original site (Zenzen 38). The plan ushered in a renewed hope that an economy spurred by tourism and the service sector could remediate the declining manufacturing industry.

Yet when the dust of fort reconstruction settled and the opening celebrations and initial elations began to fade, Rome was left with little more than an artificial relic of its past and no shopping center to speak of. The project offered relatively little tourist incentive and attraction. The idea that urban renewal could solve all of the city’s problems was facing a harsh reality, and Romans were not easy to take the news of declining tourist numbers in the succeeding decade after the project was so heavily touted by city leaders, writers, outside economic agencies, and even the National Park Service. Nation-wide factors like inflation and gas shortages didn’t help either (Zenzen 133). Yet probably most detrimental to the success of the project is the lack of scope. The economic feasibility report generated by ERA suggested that Rome develop itself into a museum town. This would include many attractions detailing the complete history of Rome, from the Revolutionary War, through Erie Canal construction, and continuous growth with cheese and copper industrial production and railroad development (Zenzen 51). I would contend that only partial investment in Rome’s historical preservation and reconstruction contributed most to languid tourist numbers. In Rome’s attempt to brand itself the City of American History, city planners probably took too much of Rome’s unique history and tossed it by the wayside, throwing all of its chips on Fort Stanwix National Monument and not developing other potential tourist attractions that could have indeed bolstered economic activity.

For instance, by the 1930s, Romans were looking for a way to gain national attention to their city by obtaining national monument status for the site of Fort Stanwix. On top of this, they were looking to develop the site into a full-scale reconstruction complete with a history museum. In 1934, the National Park Service sent investigators to report on the site and suggest whether the federal government could develop it into a park or memorial. That summer, Senator Robert F. Wagner and Representative Frederick J. Sisson both submitted bills to Congress for establishing Fort Stanwix National Monument.

The bill faced both support and opposition among lawmakers. Yet on August 21st, 1935, President Roosevelt signed the bill into law The bill allowed the land to be set aside and protected under federal regulation, while also presupposing that the government could acquire the land for eventual development into a National Monument through the Park Service. While the passing of the act was a huge step towards the ultimate goal of establishing a national monument, it was clear that at the time, for a nation still in the grips of a depression, federal funding would not be available in the near future for significant development of the site. Kessinger, who had been pivotal in pushing the one-third scale reconstruction and the bill, passed away in 1941. Also, the nation was preparing to enter the Second World War.24 While visions of a reconstructed fort faded and other issues rose to national importance, the idea was never buried.

In the years following World War II, Rome suffered from high unemployment, dilapidated city blocks, and an economically failing manufacturing industry. Early signs in the 1920s of a failing economy began to fully bloom in the 1950s and 60s. Rome’s central downtown district, the site upon which the original Fort Stanwix had stood in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century, was once characterized by stately mansions and architecturally elegant buildings. A housing shortage quickly called for the gutting and restructuring of these buildings into derelict apartments, stripping them of their former charm. In the aftermath of the First World War, the once thriving cheese industry and other agricultural industries (including cotton and wood) declined quickly. The railroads and canals that passed through Rome and contributed to its once thriving manufacturing economy would quickly become overshadowed by cars, trucks, and highways that bypassed the city. Even Rome’s renowned copper industry for which its nickname derives, began to suffer with the shift from durable goods (tools, guns, locomotive parts) to a focus on electronics parts, and the rise of plastics, stainless steel, and aluminum. Griffiss Air Force Base, which for years shielded Rome from economic disaster prior to the 1960s, finally faced its own disaster as budget cutters removed Rome Air Materiel Area. The removal represented a colossal loss of about twenty-seven hundred jobs for Rome.

Decades of neglect, urban decay, and deteriorating industrial vestiges would take its toll. In 1958, Rome became invested in urban renewal, which was the federal government’s response to post-WWII concerns of inadequate housing in deteriorating cities. Through Congress’s 1949 Housing Act and a number of amendments to the bill leading up to 1959, Rome’s southern central business district would be the target of a sweeping demolition project that removed twenty-four acres of old buildings, warehouses, junkyards, and residences. The 1967 Master Plan implemented new retail enterprises including a shopping center, restaurants, a motel, and a complete reconstruction of Fort Stanwix on its original site.26 The plan ushered in a renewed hope that an economy spurred by tourism and the service sector could remediate the declining manufacturing industry.

Yet the idea of full fort reconstruction wasn’t seriously considered to be the focal point of Rome’s urban renewal effort until late in the process. One proposal had been made to create a kind of memorial/historical park with a scaled down representation of the fort. Another proposal planned for a museum, with flashy exhibits that represented and explained the whole history of Rome, form Fort Stanwix through present-day. Another proposal suggested having the many historical buildings of Rome brought together to one location to give visitors a glimpse of the historically unique “Old Rome”. While the idea of full fort reconstruction existed, Romans wondered if there was enough documentation of what the fort looked like, where exactly it stood, and if it could be historically accurate. Rome brought in Colonel J. Duncan Campbell, an expert on Revolutionary War era military fortifications and consulting archaeologist at the Smithsonian to lead a 12 week exploration of the original site. Campbell, in his final report in 1965, stated “much of the original fort, in the form of buildings and other features, can be exposed through careful site excavation.” This was all that Rome needed to latch onto the idea of renewal through complete reconstruction of the fort.

Fritz Updike, now the editor of the Rome Sentinel, began to heavily endorse the project through his editorials, writing “only a coordinated urban renewal program such as is envisioned in this urban renewal approach will save Rome.” Of course, Fritz was mostly interested in the reconstruction of Fort Stanwix. The other aspect of the planned urban renewal project, however, involved the rebuilding of downtown block adjacent to the original site. As drawn in the city plans, the project included a public square on a parking garage, with pedestrian malls at lower elevations along the block. The idea was to attract tourists, have them park in the garage, and spend a day or a weekend in Rome vising historic sites and spending money at the outdoor mall. This outdoor shopping plaza was not unprecedented, it reflects a planning strategy undertaken by a number of cities across the country with the same intent: to spur economic growth. The first outdoor pedestrian shopping mall in the United States was built in Kalamazoo, Michigan, designed by Victor Gruen. Opening in 1959, the goal of the plan was to translate the city center into something of a pedestrian zone, where shoppers could park their cars and spend the day shopping. It was an attempt to reverse suburbanization, one of the major obstacles faced by a number of declining downtown districts throughout the U.S. at the time. The initial success of the project was alluring for a lot of city planners, and Gruen’s office received much demand for implementation of the same model across the U.S. Rome, as well, could not help but look upon the project with envy and hope for their own outdoor shopping mall. The vision of this pedestrian mall was rendered by Hueber Hares Glavin and Associates

Before and After image of Rome, prior to reconstruction (1969) and after (1976). (History & Culture).

“Greenbacks not redcoats” Article giving a brief overview of the later stages of the fort reconstruction. (Greenbacks, not redcoats).

Daily Sentinel Article about President Roosevelt’s approval of the Wagner-Sisson Act (Updike, Fritz).

Existing Use Map, plotting the location and describing the condition of buildings to be razed by the urban renewal project (Candeub, Fleissig and Associates).

A view down James Street in 1960. All of these buildings shown were to be razed in the spirit of urban renewal. (History and Culture).

Plan of 1758 Fort Stanwix, signed by Jn. Williams Sub-engineer. The plan probably represents how the fort looked after the initial round of construction. (Carroll).

Project Revenue Sheets 1, 2 show the ERA’s flawed miscalculations in both tourist numbers and revenue for Rome. (Economics Research Associates).

Project Revenue Sheets 1, 2 show the ERA’s flawed miscalculations in both tourist numbers and revenue for Rome. (Economics Research Associates).

Reenactor Lester Mayo in his Third New York Regiment uniform talks about the fort’s cannon to onlooking schoolchildren. (Zenzen).

Site Plan and Perspective drawn by Orville W. Carroll’s architectural office for the proposed reconstruction. (Waite).

Urban Renewal Area Plan detailing the extensive nature of the proposed development of Rome’s CBD. (U.S. Department of the Interior).

Bibliography

- Analysis of Economic and Urban Renewal Potentials of Rome, NY. Los Angeles: Economics Research Associates, 1966. Print.

- Candeub, Fleissig and Associates, Hueber Hares Glavin Partnership, and Newman and Doll. Fort Stanwix Central Business District Project, City of Rome, New York. N.p.: n.p., 1972. Print.

- Carroll, Orville W. Fort Stanwix, Architectural Data Section: Fort Stanwix National Monument, Rome, New York. Denver: Denver Service Center, Historic Preservation Team, National Park Service, U.S. Dept. of the Interior, 1973. Print.

- Curley, Robert W. “Fort Work Pricetag Building.” The Syracuse Herald [Syracuse] 20 July 1975, sec. 5: 51. Print. Obtained by http://www.fultonhistory.com/Fulton.html

- “Greenbacks, Not Redcoats: Fort Awaits Invasion.” The Syracuse Herald-Journal [Syracuse] 11 Sept. 1975, 22-N sec.: n. pag. Print. Obtained by http://www.fultonhistory.com/Fulton.html

- “History & Culture.” National Parks Service. National Parks Service, 10 Apr. 2013. Web. 24 Apr. 2013. .

- Leonard, Peter M. Rome Revisited. Charleston, SC: Arcadia Publishing, 2007. 128. Print.

- “NPS Stats Report Viewer.” NPS Stats Report Viewer. NPS, n.d. Web. 06 Apr. 2013. .

- “Rome Council Votes Survey of Tourism Potential.” Syracuse Herald-Journal [Syracuse] 27 Aug. 1965: 26. Print. Obtained by http://www.fultonhistory.com/Fulton.html

- United States Department of the Interior, and National Park Service. Fort Stanwix National Monument a Master Plan. N.p.: n.p., 1967. Print.

- Updike, Fritz S. “Roosevelt Signs Ft. Stanwix Bill.” Rome Sentinel [Rome, NY] 22 Aug. 1935: 2. Print. Obtained by http://www.fultonhistory.com/Fulton.html

- Waite, Diana S. History of a Nineteenth Century Urban Complex on the Site of Fort Stanwix, Rome, New York,. [Albany]: New York State Historic Trust, 1972. Print.

- Zenzen, Joan M. Fort Stanwix National Monument: Reconstructing the Past and Partnering for the Future. Albany: State University of New York Press, 2008. 298 pages. Print.