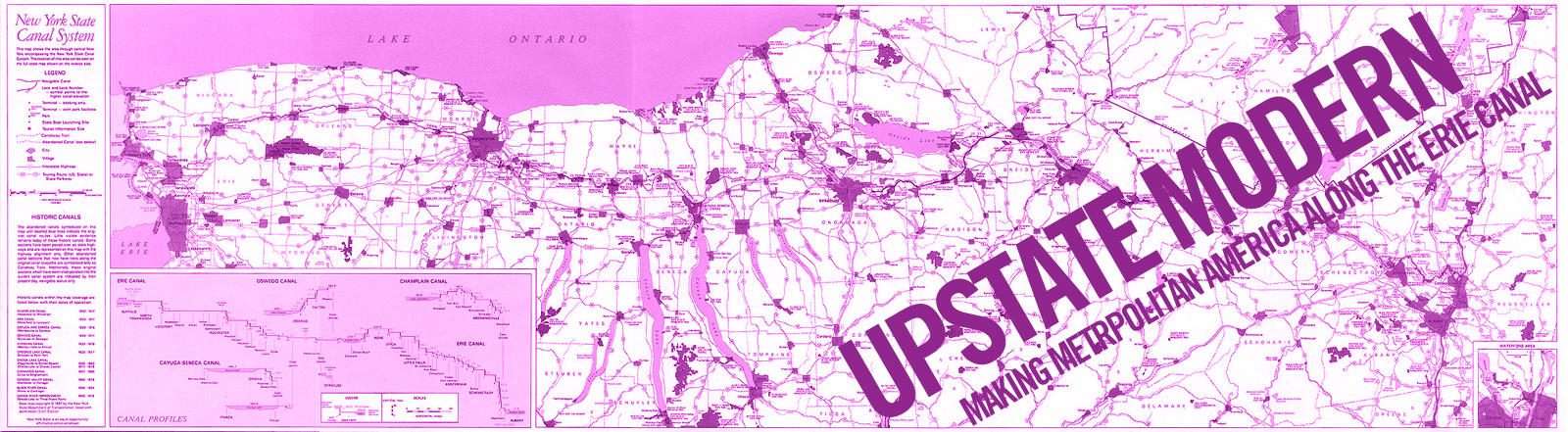

Upstate Modern MAKING METROPOLITAN AMERICA ALONG THE ERIE CANAL

Upstate Modern is a series of courses and public programs at Syracuse University examining the urban history of Upstate New York through transdisciplinary research that draws on archives, buildings, landscapes, and communities.

Demolishing Buffalo’s Larkin Building

By Joshua Rubbelke.

From its construction in 1906 through its demolition in 1950 to its potential reconstruction, Frank Lloyd Wright’s Larkin Building epitomizes Buffalo’s changing economy.

In the early 1900’s, industrial cities were booming with productivity and populations were at an all-time high. Cities like Detroit, Syracuse, and Buffalo were growing due to the amount of work available in the industrial business. Now, these once prosperous cities are becoming wastelands of tall, brick buildings; decaying and obsolete.

One company in Buffalo, New York, the Larkin Soap Company, was one of these prosperous factory companies. They invented a mail order company for families to order their products by mail. As a sign of their power and success, they hired Frank Lloyd Wright to design an administration building to manage the mail order business. The Larkin Administration Building was built in 1906 but its life didn’t last long. When the Great Depression hit, the Larkin Company took a toll and eventually went bankrupt. The building became obsolete and so the Larkin Administration Building went up for sale but failed to find a buyer with a good enough price; the highest bidder offering $25,000. Finally, the Western Trading Corporation offered $5,000 to buy the building promising to build a $100,000 truck terminal. The obsolete site was to be transformed into something better. Unfortunately, the Western Trading Corporation moved their site after the Larkin Building had been demolished so the site became a parking lot; catering to the automotive industry and the push for middle class to own vehicles.

Like many other buildings in “shrinking cities,” the story of the Larkin Building is more than just a story of the decline of a building; it is also the story of the decline of a city. Presently, efforts are being made to recreate the Larkin District. The Larkin Building has been talked about as part of this rebuilding effort. Could this be seen as an effort for Buffalo to return to the prosperous city it once was?

In the early 1930’s, the development of cross-country highways, the rise of the trucking industry, and the opening of a major shipping canal in Ontario that circumvented Niagara Falls each contributed to the weakening of Buffalo’s position as a vital Great Lakes port city and railroad center. The filling of the Erie Canal stopped all trading by boat from Eastern New York, though most shipping was already declining because of the canal in Ontario. The decline of the railroad was seen as early as 1916 when the railroad system registered its first decline in active track-age since 1830. The two world wars as well as the depression masked the decline of the railroad. However, even in the years of the depression, the shift to truck transport had already become noticeable enough that in 1939, a federal commission proposed the building of the future Eisenhower Interstate Highway system because truck traffic was clogging up the nation’s roads. As the highways grew, the carload traffic fled the railroads. Oil and chemicals began to be transported by pipes and trucks, and grain was transported by barge. Goods that were once transported in an iced boxcar were being transported in an air conditioned tractor trailer and, of course, passengers that were transported by rail were transported quickly and easily by personal car and planes. The conditions that led to the popularity of the Larking mail-order business began to change as well. The chain stores that were originally only available in the city began to expand to the suburban neighborhoods where people had been moving and the increasing number of automobile ownership made it possible for people to travel into the city when the stores were not nearby. The increase in stores also meant the decrease in prices because of the high availability of the products; the Larkin Company couldn’t stay competitive (Quinan, p.119).

The Larkin Company’s internal problems were no less hectic than what was happening in the Buffalo economy. The beginning of the decline of the Larkin Building can be traced back to the late 1920’s. As a family man, John D. Larkin wanted to keep his company in the ownership of his sons and son-in-laws. This approach to business unfortunately led to the undoing of the Larkin Company. Real turmoil in the Larkin Company began in 1924, when William Heath, office manager since 1902, suddenly retired. Darwin Martin followed suit in 1925 after getting into a heated argument with John D Larkin Jr. during a director’s meeting. Three key members in the secretary department retired shortly after Martin’s leave. In short, John D Larkin Jr. brought about the retirement of most of the men who had been lead figures in the development of the mail-order business. In 1939, the Larkin Retail Store, located at 701 Seneca Street, was moved across the street into the Larkin Administration Building because there was “25% more floor space.” The administration made the argument that because of the rapid elevator in the building and the large amounts of natural lighting, that the store would become one of the most attractive retail establishments in the country. Because of this move, extensive remodeling of the interior began. From the time of remodeling in 1939 to 1943, business began to dwindle and the Larkin Company fell further into financial troubles. By 1943, officers of the company had already started selling off buildings that the company had owned so it didn’t surprise anyone when the Larkin Company was sold for an undisclosed sum to L.B. Smith, a Harrisburg, Pennsylvania contractor. When the building was bought out, it still had nine months remaining on its lease. When the nine months ended, Smith abandoned the building until it was taken over in a tax foreclosure of $104,616 by the city of Buffalo on June 15th, 1945 (Puma, p.10).

The next time the building appeared in the news was on November 1, 1946 when the city comptroller reminded people that the building was for sale at an estimated $226,000. By then only one offer had been made; an offer of $26,000 from an unknown prospect. In an attempt to lure potential buyers, the city spent $6,000 an advertising campaign featuring “for sale” ads appearing in all the newspapers in Buffalo. By March 29, 1947, the city had received no offers to buy the building and was beginning to panic. They desperately asked many businesses to buy the building and remodel it to fit their needs but every offer was turned down. By October 1947, the “White Elephant” was almost totally useless. Every double-paned window was shattered, the entrance gate was toppled, and the iron fence topping the brick wall around the structure went into a wartime scrap collection. Twenty tons of copper plumbing and roofing, along with anything else of value, were also stolen. It became a site where neighborhood children would play among the rubble and throw bricks at visitors passing through the site. Jack Quinan states in his book Frank Lloyd Wright’s Larkin Building, that “there is no reason why this spectacle of decay cannot be amended, so that at least the Larkin Building need not look like the result of deliberate inattention on the part of public authorities” (Quinan, p.126). When the city opened up a cheaper buying option, the potential buyers started contacting them. Unfortunately, the city comptroller felt that nothing was good enough, probably a money-making scheme… but that is just a speculation. By March, 1949, the city had rejected offers for the building to become emergency housing, a welfare department, a brewing company, and a recreation center to house the boys throwing the bricks at visitors and raise them to become respectable men. Another suggestion by Ralph A Coppola to transform the building into a Buffalo Conservatory of Music was also rejected. 6 months later, on September 13, 1949, the city sold the building to the Western Trading Corporation for $5,000 with the promise of also building a $100,000 “taxable improvement” (Puma, p.12).

The corporation estimated that it would cost $100,000 to demolish the building, and it was noted at this time that everything removable had been stripped by vandals. This included 20 tons of copper, light fixtures, door knobs, plumbing, and even the boards used to keep the vandals out. Also, it was estimated that it would cost $8,000 to replace the windows. The final sale was made on November 15, 1949 and the site of Wright’s beloved Larkin Administration Building was set to be demolished (Puma, p.12).

Even though the building was vacant for seven years, public outcry only began after plans to demolish the building were set in place. On November 16, 1949, architect J. Stanley Sharp stated in an article in the New York Herald Tribune:

As an architect, I share the concern of many others over the destruction of Frank Lloyd Wright’s world famous office building in Buffalo. It is not merely a matter of sentiment; from a practical standpoint this structure can function efficiently for centuries. Modern engineering has improved upon the lighting and ventilation systems Mr. Wright used, but that is hardly excuse enough to efface the work of the man who successfully pioneered in the solving of such problems. The Larkin Building set a precedent for many an office building we admire today and should be regarded not as an outmoded utilitarian structure but as a monument, if not to Mr. Wright’s creative imagination, to the inventive-ness of American design (BEN, November 16, 1949, from Library files).

Demolition of the Larkin Building began in late February, 1950 by the Morris and Reimann Demolition Company of Buffalo and was completed in July 1950. This unusual, lengthy demolition was due to the fact that the building was “built to last forever.” Fire Lieutenant William J. Jackson of Engine 32, Seneca and Swan Streets said, “That was built, that building! The wrecking ball would bounce off it, it was that well reinforced” (BEN, August 25, 1972, p.1). The floors in the building were made up of ten inch thick reinforced concrete in slabs that were seventeen feet wide and thirty-four feet long. The floors were supported by twenty-four inch steel girders, which are now shoring up the mines in West Virginia. The bricks that were used to construct the Larkin Administration Building were used to fill in the Ohio River Basin to make way for Conway Park (Quinan, p. 128). I recently visited Conway Park in Buffalo and the graveyard of Wright’s bricks has become a desolate, dirty, and unattractive space. The park is surrounded by abandoned factory buildings and it has now become a place of high crime.

In May 1951, one year after the demolition, the Western Trading Company announced plans to build a truck terminal on the site. The building’s plans, built by I.A. Germoney, showed an L-shaped building with a frontage of 280 feet on Seneca Street and extending 280 feet to Swan Street where the frontage would be 50 feet. A fifty foot by seventy foot section of the terminal would include two stories, housing the offices on the upper floors. The estimated cost of the terminal was $150,000 to $200,000 (Puma, p.13).

On November 24, 1951, the Western Trading Company petitioned to allow the city council to change the site of their truck terminal from the Larkin site to a site at Elk and Dole streets because “it was less crowded.” They also stated in their petition that if they did build the terminal on the Larkin site, a valuable parking lot for the customers and employees of the Larkin Terminal Warehouse would be lost. Three days after the submittal of this petition, the city council approved the plan making the demolition of the Larkin Building pointless and gracing Frank Lloyd Wright’s Larkin Building site with a parking lot; one that is still unused today (Puma, p.14).

Article about the moving of the terminal site. The announcement of a parking lot being created is also in this article.

Buffalo Evening News

Bibliography

- Abramson, Daniel M. “Boston’s West End Urban Obsolescence in Mid-Twentieth-Century America.” Governing by Design. ; Architecture, Economy, and Politics in the Twentieth Century. N.p.: University of Pittsburgh, 2012. 47-66. Print.

- “The Buffalo History Gazette.” : October 2011. N.p., n.d. Web. 05 Apr. 2013.

- “Frank Lloyd Wright and His Forgotten Larkin Building.” Bearings RSS. N.p., n.d. Web. 05 Apr. 2013.

- PBS. PBS, n.d. Web. 05 Apr. 2013.

- Puma, Jerry. “Larkin.” Larkin. N.p., n.d. Web. 05 Apr. 2013.

- Quinan, Jack. Frank Lloyd Wright’s Larkin Building: Myth and Fact. New York, NY: Architectural History Foundation, 1987. Print.

- “Western New York Heritage Press.” Western New York Heritage Press. N.p., n.d. Web. 05 Apr. 2013.