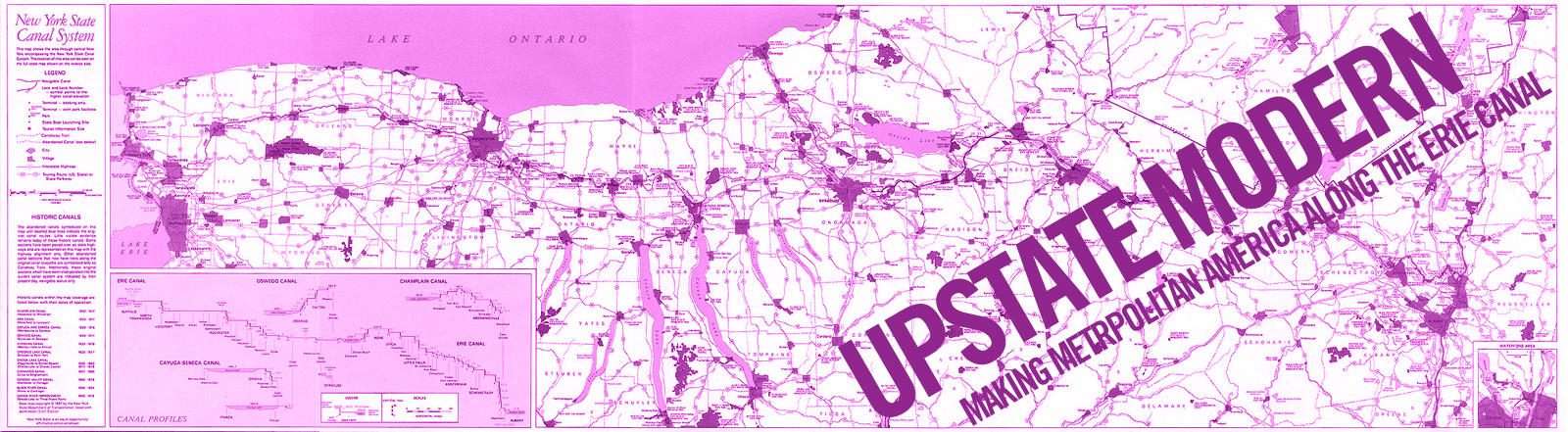

Upstate Modern MAKING METROPOLITAN AMERICA ALONG THE ERIE CANAL

Upstate Modern is a series of courses and public programs at Syracuse University examining the urban history of Upstate New York through transdisciplinary research that draws on archives, buildings, landscapes, and communities.

Attica: The Unlearnt Lessons of the 1971 Revolt

By Andres Jaime.

“The rebels armed in advance with knives, spears, clubs, swords, steel and metal pipes, pickaxes, shovels, straight razors, wire bolos and baseball bats with extended spikes took… control of A, B, D and E Blocks within twenty minutes. Then the rebels attacked the commissary, metal shops, industrial buildings and set fires to the auditorium, chapel and school house…After a sharp struggle, the rebels took C Block. They had won control of most of the maximum security institution within thirty minutes.”

-Commissioner Russell G. Oswald

Retrieved artifacts from the revolt. Images taken from: Truckloads of Attica’s agony Artifacts from the deadly 1971 prison riot arrive at State Museum, by PAUL GRONDAHL Staff writer. Published in www.timesunion.com, 12:01 am, Thursday, September 29, 2011. (url: http://www.timesunion.com/local/article/Truckloads-of-Attica-s-agony-2194152.php#photo-1633595)

After 1971, there was an increase of state funds to the Department of Correction, but in reality this money was not used to actually fix what was previously broken. Paradoxically, this money helped reinforce the already in place custodial model, giving only some basic concessions to the inmate population. The important discussions that arose after the revolt were regarding the polarization in the Legislature between rehabilitation or pro-inmate interest versus the defense of the custodial model. Five months after Attica, Governor Russell G. Oswald stated that a total of 339 new corrections officers had been hired, thousands of gas masks and helmets had been delivered to a number of institutions and negotiations for better metal detectors had started. At the same time, food conditions were improved for inmates, an increased number of showers per week, expanded clothing and toilet paper benefits. Considering the previous allowance of one shower per week, one roll of toilet paper every 5 weeks, inedible food (according to The New York State Special Commission on Attica), and the ban of blue attires by the prisoners, these early resolves to revert the existing conditions was positive and humane. But in reality, these measures were not rehabilitating in nature, they were just raising the living conditions from an infra-human level to a regular standard, while at the same time, the custodial aspect became stronger and tighter. Was the tragedy not enough to actually produce a profound change in the system immediately after the events?

A number of artifacts from this event were confiscated, tagged, and stored. Almost 42 years after Attica, these items acts as gateways to go back to that time, and re-live, re-interpret and remember what happened.

It seems as the revolt acted as a flash of truth about the prison system and all that was wrong with it, and although there was a lot of commotion and promises made in order to revert the now ‘revealed’ horrors, the “system had remained fundamentally the same.” Apparently the thing that Attica did help change is the public address to issues regarding imprisonment and correctional facilities and its conditions, but “in the realm of real politics and popular interests, prison conditions and policies continued to have a low priority despite lip service to their importance.”

For instance, The “birdcage” metaphor is helpful to understand racism and the incarceration machine that Attica helps unveil. Theorist Iris Marion Young explains that its hard to understand racism if we understand each racial disadvantage as a single wire of the cage. The only way to grasp the reality is by understanding a number of wires and how are they connected to each other, rendering the cage a true inescapable place for the bird. Attica’s revolt was an event that broke one of the wires, but then was quickly fixed, fastened and made stronger. The cage was fixed, and the public didn’t even notice.

There are some complex realities working in relation to the event. In 1973 Governor Rockefeller supported and passed a number of statutes that were known as the Rockefeller Drug Laws. These dealt with the handling of narcotic drugs in the New York State, and were aimed to be the toughest laws of this kind in the US. Rockefeller Drug Laws placed offenses regarding possession and sale of narcotic drugs in the same level as murder in terms of conviction times. The War on Drugs is one of the wires, it is “the vehicle through which extraordinary numbers of black men are forced into the cage” . Police departments conduct drug operations primarily on poor communities of color. Arrests then happen in very concentrated areas sometimes, and in cases the concentration is so dense that states are spending more than a million dollars a year to incarcerate the residents a single city block. When these people are released and reenter their communities, roughly forty percent do not stay more than three years before they are reincarcerated.” Police officers can choose to stop and search anyone they consider for drug investigations, resulting in an uncontrolled racially biased police enforcement. Crimes that can be committed by anyone are then attributed to black or latino communities. This is the first step in mass incarceration, which constitutes a perfectly legal form of discrimination, invisible but tangible, and it is one of the wires of the cage.

The situation does not improve once the inmate serves the sentence. Before and during a large portion of the twentieth century, the prison system in place was the Auburn system, a system that originated in New York in 1826 and later became a model for the world. This system was based on obedience and subordination from the inmate, an entirely custodial model, with no rehabilitating intentions. Of course “the consequence of this system was an atmosphere of despair among inmates, many of whom felt caught in an unending cycle of crime and punishment.” Another wire in the cage. It was argued that the system only trained the inmates for survival in prison, but nothing was further from rehabilitation in order to get reinserted in society. This resulted in high percentages re-incarcerations, which basically meant the removal from society of those individuals. Those prisoners that actually try and make it out of that cycle, they are denied employment and are never quite able to fit back into the mainstream society, are then forced back in due to lack of opportunities that the system itself provides for former convicts. As ere explains, “the formerly incarcerated could have their employment options reduced by as much as 59 percent and, if hired, their annual income reduced by as much as 28 percent, and their hourly wages reduced by as much as 19 percent.”

Another wire in the cage is the issue of prison construction as economic developments in shrinking cities in the late post-war period. As cities’ industries waned, the new business that could support or make a city bloom was prison state. Heather Ann Thompson argues that “during the later postwar period, annual meetings of the American Correctional Association became little more than trade shows where for-profit firms hawked their goods and services. Whether a business sold bricks and mortar, or barbed wire, or uniforms, or beds, or sophisticated architectural plans for more secure penal facilities, the carceral state was a boom.” In the same article Thompson explains that the the early 1970s there were only two prisons in the Adirondack district of upstate New York, but by the late 1990s it had eighteen correctional facilities and one more in construction. This tremendous growth in prison development in the Upstate New York region, of course, demanded a growth in inmate population. This demand was easily met by a system that was already in place. Big cities in the New York State region produce criminals that are housed in prisons scattered in the Upstate New York, thus allowing for economic development of such areas.

Bibliography

- UNSDRI Prison Architecture. Various Authors. The Architectural Press Ltd, London. 1975

- A Time to Die. Tom Wicker. Quadrangle/The New York Times Book Co., 1975.

- Correctional Reform in New York: The Rockefeller Years and Beyond. Barbara Lavin McEleney. University Press of America, Inc. 1985

- Building Type Basics for Justice Facilities. Todd Phillips, Stephen Kliment, Michael Griebel. John Wiley & Sons, Inc Hoboken, New Jersey, 2003.

- Attica: The Official Report. Tom Murton. The Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology (1973-), Vol. 64, No. 4 (Dec., 1973), pp. 494-499. Publisher(s): Northwestern University. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1142450

- “The Order of Attica”. Robert P. Weiss. Social Justice, Vol. 18, No. 3 (45), Attica: 1971—1991 A Commemorative Issue (Fall 1991), pp. 35-47. Publisher(s): Social Justice/Global Options. http://www.jstor.org/stable/29766618

- Episodes From The Attica Massacre. The Black Scholar, Vol. 4, No. 2, BLACK PRISONER (II) (October 1972), pp. 34-39. Publisher(s): Paradigm Publishers. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41163594

- Michel Foucault on Attica: An Interview. Michel Foucault; John K. Simon. Social Justice, Vol. 18, No. 3 (45), Attica: 1971—1991 A Commemorative Issue (Fall 1991), pp. 26-34. Publisher(s): Social Justice/Global Options. http://www.jstor.org/stable/29766617

- Attica and Prison Reform. Gerald Benjamin and Stephen P. Rappaport. Proceedings of the Academy of Political Science , Vol. 31, No. 3, Governing New York State: The. Rockefeller Years (May, 1974) Published by: The Academy of Political Science, pp. 200-213. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1173220

- Attica Prison Riot. (2002). In World of Criminal Justice, Gale. Retrieved from http://www.credoreference.com/entry/worldcrims/attica_prison_riot

- Attica Revisited website http://www.talkinghistory.org/attica/index.html

- Emily Kunstler and Sarah Kunstler, William Kunstler: Disturbing the Universe (2009): excerpt on Attica Prison Rebellion in http://www.pbs.org/pov/disturbingtheuniverse/additional_video1.php#.USJQIaXCZ8F

- All images were taken from: Truckloads of Attica’s agony Artifacts from the deadly 1971 prison riot arrive at State Museum, by PAUL GRONDAHL Staff writer. Published in www.timesunion.com, 12:01 am, Thursday, September 29, 2011. http://www.timesunion.com/local/article/Truckloads-of-Attica-s-agony-2194152.php#photo-1633595