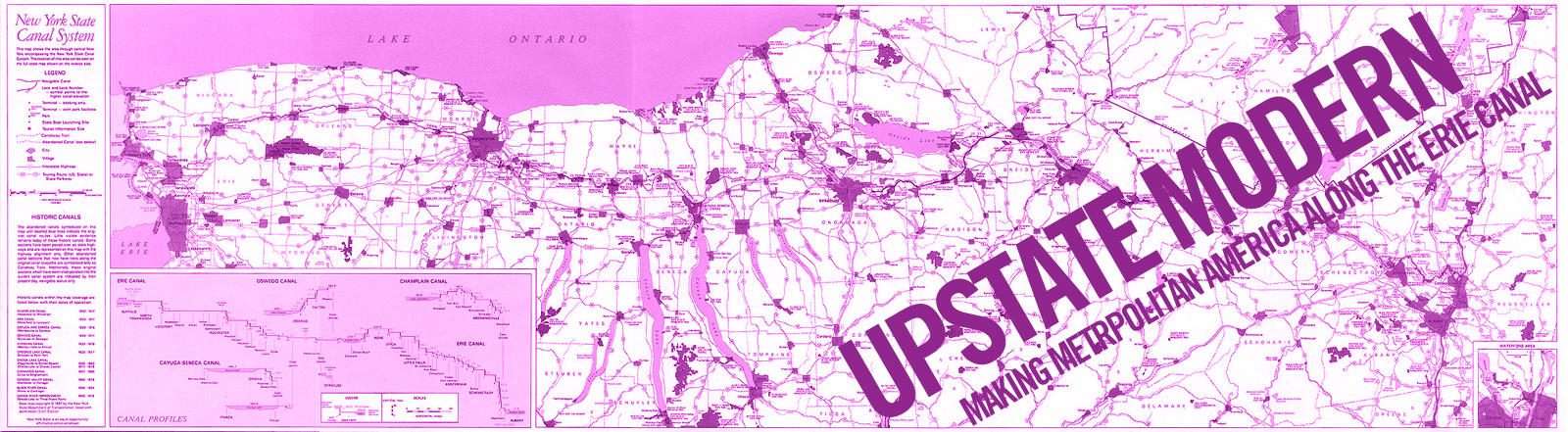

Upstate Modern MAKING METROPOLITAN AMERICA ALONG THE ERIE CANAL

Upstate Modern is a series of courses and public programs at Syracuse University examining the urban history of Upstate New York through transdisciplinary research that draws on archives, buildings, landscapes, and communities.

Carousel’s Destiny: Syracuse and its Megamall

By Alex Sabo.

Destiny USA, once known as the Carousel Center, is one of the staples of Syracuse. Since its opening in 1990, Destiny has become the sixth largest mall in the world. It has followed the Mall of America model of expanding beyond retail and incorporating entertainment, recreation facilities, and restaurants into the mix. The size of the super-regional center and the impact that it has on Syracuse and its economy has led to a complicated and controversial relationship between Pyramid Management, the owner of Destiny USA, and the city of Syracuse. Government programs initiated at the local, state, and federal levels, including property tax exemptions, tax credits from the state Empire Zone program, tax-exempt federal “green bonds”, and tax credits under the state’s Brownfield Cleanup Program, have caused taxpayers to question Destiny’s contribution to the community. What might be overlooked is the social dynamic that Destiny provides—a type of civic space that is representative of the city centers, marketplaces, and downtowns that have permeated our civilization.

Aerial view of the Carousel Center on opening day, October 15, 1990. Carl Single / The Post-Standard

Destiny USA’s four floors of retail combine department stores, specialty stores, restaurants, and entertainment venues to create an atmosphere that provides a unique social function. The planning that necessarily accompanies the mixing of tenants is essential for the mall’s success as a social destination. Likewise, the planning of the city of Syracuse is important, as better planning drives more people into Syracuse and Destiny. Hotel packages and shuttles to the mall are examples of planning outside the mall to generate business. Destiny is involved in city politics because of the economic impact it has on the city. Studies have looked at how malls affect surrounding property values, and besides the immediate properties, which suffer an increase in noise pollution and congestion, the community as a whole generally sees higher property values. Therefore, the argument has been made by Destiny that in order to make back what they put into the community they require special tax arrangements. A PILOT program was developed as an alternative to property taxes, and several state programs have allowed Destiny to claim tax credits for (1) developing the brownfield site beside Onondaga Lake known as Oil City, and (2) providing Syracuse with a tourist attraction. Additionally, Destiny has received $228 million in tax-free financing from a federal “green bond” program for their use of sustainable technologies.

Destiny USA might be considered a planned downtown, mall, power center, and lifestyle of entertainment all under one roof. It is owned by Pyramid Management, which leases out units to retail merchants. The large tenants are anchor stores; they draw traffic to the mall and are positioned at the corners of the mall. They are located away from each other in order to spread customers throughout the mall. In Destiny, the anchor stores are JCPenney, Macy’s, Lord & Taylor, Best Buy, The Bon-Ton, Dick’s Sporting Goods, Sports Authority, Forever 21, DSW, Old Navy, Finish Line, and Off 5th. The smaller stores are grouped according to many things, such as: compatibility with other stores and potential for impulse buying. The shared amenities between the retailers are controlled through centralized management, allowing the mall to make design and policy decisions that affect the overall mall.

The mall is able to plan large-scale projects (electricity, water, sewage, transportation, security, trash collection, etc.) because it doesn’t subdivide its property, but rather leases out units within its property. Therefore, because the mall owns the units, it has a reason to engage in ‘public works’ that increase the value of the units, from which the mall can collect higher rents. Town planners and councilmen, like residents, own individual lots instead of the land as a whole. As a result, their planning, whether helpful or harmful, has little impact on their holdings. To the extent that mall improvements attract customers, and to the extent that the increased traffic makes leasable space more valuable, the potential for higher rent will continually spur investments traditionally assigned to local governments. As malls like Destiny USA become larger and larger, and their services further approximate those of local governments, the distinctions between them will blur. The mall, especially in Destiny’s final proposal, then, is more than a mall, and its reasons for receiving tax money more easily meshes with those of libraries and schools.

As a result, envisioning malls as public space attributes certain responsibilities to them that have traditionally been confined to city property. In this sense, “public” refers to access. It refers to what you can do in a space. For example, a military base is fully government-funded, but it is not public in terms of access. You cannot just visit it; and often you can’t even photograph it or know whether it exists at all. Malls, on the other hand, like universities, are intended to be places of free expression. Not only should they be fairly accessible, but they should also be fairly tolerant of what can be done on the property. Courts have ruled that even though malls own their property, they still must allow certain behavior. This seems consistent with public life and the ability of those who feel wronged to pursue legal action. Different states have different policies depending on how they have interpreted and applied their state constitutions. Some states have interpreted free speech very broadly while others have backed off.

Like state governments, malls also want to attract people and business. If a mall enforces an overly strict speech code, then visitors will avoid being hassled by security and go somewhere else. In the same way, if malls go too far in the other direction, then visitors will face congestion and non-stop Envisioning malls as public space attributes certain responsibilities to them that have traditionally been confined to city property. In this sense, “public” refers to access. It refers to what you can do in a space. For example, a military base is fully government-funded, but it is not public in terms of access. You cannot just visit it; and often you can’t even photograph it or know whether it exists at all.

Malls, on the other hand, like universities, are intended to be places of free expression. Not only should they be fairly accessible, but they should also be fairly tolerant of what can be done on the property. Courts have ruled that even though malls own their property, they still must allow certain behavior. This seems consistent with public life and the ability of those who feel wronged to pursue legal action. Different states have different policies depending on how they have interpreted and applied their state constitutions. Some states have interpreted free speech very broadly while others have backed off. Like state governments, malls also want to attract people and business. If a mall enforces an overly strict speech code, then visitors will avoid being hassled by security and go somewhere else. In the same way, if malls go too far in the other direction, then visitors will face congestion and non-stop Malls take the place of town squares, parks, streets, and other spaces that are publicly owned. That should imply a heavy responsibility. Putting limits on speech—even when you have the right to do it—is dangerous. Restrictions that do not reflect the community are not only dangerous for the mall’s success, but because the mall is so tied to the community, its near monopoly position makes it dangerous for the city as well.

The list of services and restrictions that apply to guests of Destiny USA in many ways reflect what the public expects from public places. Since the mall is designed to attract visitors, the conflict is not necessarily between the mall and its shoppers, but between some shoppers and other shoppers. Many shoppers do not want to be bothered by these things like petitions and demonstrations. This is true even of completely public things. There are rules about what can and cannot be done in parks, libraries, and roads, despite the fact that these places are both publicly funded and publicly accessible. Protest permits are required to organize demonstrations, and once issued, they often corral protesters into “free speech zones”, common in public universities, in which the protesters have little visibility and impact. Another example might be videotaping police or public buildings. Despite the public nature of these things, actions still have consequences; and acting in a way that upsets a policeman, regardless of what you call it, may be seen as interfering with official police conduct and get you tossed in jail. According to the First Amendment Center, issues over what can and cannot be done at malls “address a question still being worked out in courts around the country: Is the local mall the modern equivalent of history’s town square, or is it just a giant bubble of private property?”

The federal courts have held that the First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution says “Congress shall write no law…”, however state constitutions have their own language regarding free speech, and many courts have understood these protections to apply to malls. In 1994, the New Jersey Supreme Court held that, “Although the ultimate purpose of these shopping centers is commercial, their normal use is all-embracing, almost without limit, projecting a community image, serving as their own communities.”17 This seems particularly descriptive of Destiny USA with its combination of entertainment, recreation, and fine restaurants. Dynamos like Destiny USA encompass so much of the community’s activity that they dwarf what alternatives exist in the city or town. In many towns, the mall is the only high-traffic area, and as a result, the legal distinctions between malls and downtowns and public vs. private are less apparent.

The fact that the mall is a centrally planned community that receives tax subsidies might resonate with some political ideologies; however, the entrepreneurial aspect of it seems to trump the subsidies and open-ended court rulings. It is not yet public enough. Closer ties need to be made between the mall and the city in order to curb the developer’s greed and self-interest. To the extent that the mall’s interests are not directly tied to the community’s self-interest through land ownership, it may be at odds with facets of the city. In other words, if mall investments benefit other peoples’ property, the mall asks for that money back through subsidies which communities compete to provide. Likewise, if mall investments harm the community, the table turns, and residents are prompted to ask for money from the mall. But not all residents agree. Some have argued that Destiny USA’s thirty-year tax exemption plan is far too favorable to the developers, while others have argued that it is not favorable enough. The land-values are not internalized like in the mall model, and so these decisions are not with central management, but with thousands of residents who petition their representatives. City officials try to gauge the support and act accordingly, but they are acting for other people. They’re administering other people’s property. They’re not acting for their own self-interest—public choice theory aside. Whereas this aspect of politics is praised for its altruism, it might be more comforting for residents, like it is with mall tenants, to know that their planners do not need to sacrifice themselves in order to build a successful community.

Developer Bob Congel discusses plans to transform Oil City with then Syracuse mayor Tom Young, 1988. Source: The Post-Standard, 1988.

Bibliography

- Colwell, P.F., Gujral, SS. and Coley, C. (1985) The Impact of a Shopping Center on the Value of Surrounding Properties. Real Estate Issues, 10(1): 35-39.

- De Maria, Kat. “Syracuse’s Carousel Center History,” 12/26/2011. centralny.ynn.com

- Haynes, Joel and Salil Talpade, “Does Entertainment Draw Shoppers? The Effects of Entertainment Centers on Shopping Behavior in Malls.” Journal of Shopping Center Research 3.2 (1996).

- Maitland, Barry. Shopping Malls: Planning and Design: (Trade Cloth, 1985).

- “The Facts on Regional Malls and What They Say About the Vitality of the Concept.” ICSC White Paper (January, 2005).