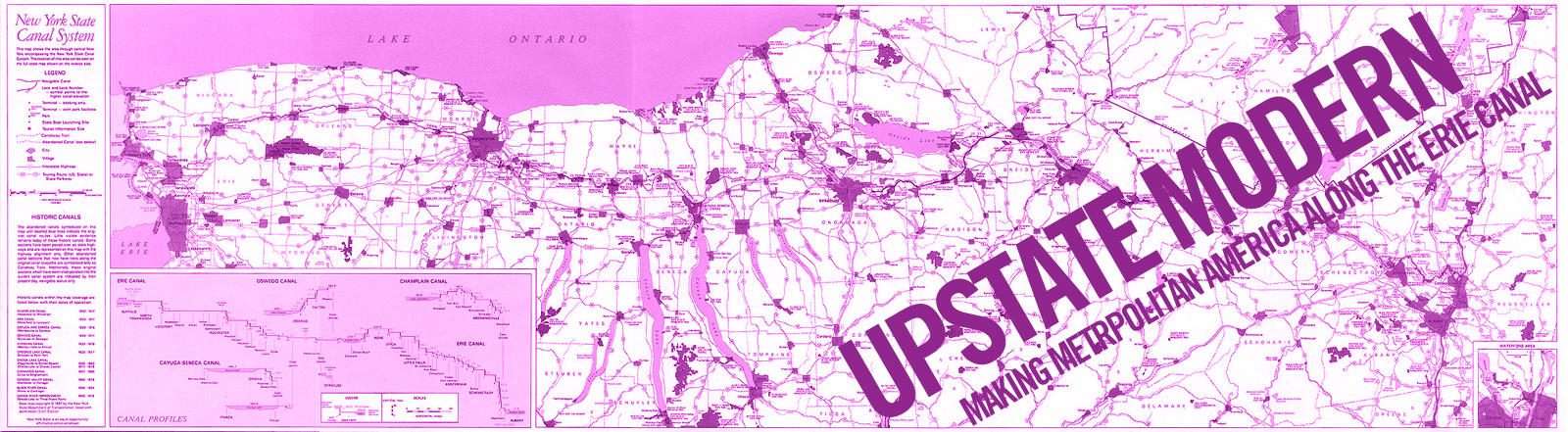

Upstate Modern MAKING METROPOLITAN AMERICA ALONG THE ERIE CANAL

Upstate Modern is a series of courses and public programs at Syracuse University examining the urban history of Upstate New York through transdisciplinary research that draws on archives, buildings, landscapes, and communities.

Sergei Grimm’s Post-War Planning

By Nate Heffron.

The landscape of American metropolises was undergoing profound changes during the mid-20th century. Throughout this period—especially following World War II—urban planners were at the fore of projects that altered cities in ways that have lasted until this day. Certain planners were ascending as pioneers in the trends of suburbanization, highway construction, urban renewal and more. In Syracuse, Sergei Grimm used his positions at the Syracuse Housing Authority (SHA) and as member of the Syracuse Post-War Planning Council to affect these changes in the city. Through an examination of planning documents and maps, we can liken Grimm to other marquee urban technocrats of the era and situate Syracuse into broader trends that were occurring in the United States at the time.

Home Owners’ Loan Corporation Appraisal of Syracuse

A map of residential security (and by extension, desirability) with Sergei Grimm as cartographer.

HOLC (1937) with digital copy provided by K. Animashaun Ducre

The artifacts that paint the picture of planning ideologies of this time come in the form of planning documents such as reports and comprehensive plans that were authored or co-authored by Grimm, as well as maps and drawings made by Grimm that reflect a spatial perception of the city and the future it should have. The artifacts used in this curation—most of which coming from Syracuse University Library’s Special Collections Center—are documents, plans and maps from Grimm’s tenure at the SHA as well as position of Executive Director of the Syracuse-Onondaga Post-War Planning Council. The pieces that this study will highlight deal with matters of transportation, zoning, housing, and also some of Grimm’s later writings on Urban Planning as a scientific discipline. The rich assortment of these artifacts will guide us to a better understanding of the goals and agendas of Grimm and other like-minded planners of this epoch.

This examination is necessary to attain a better understanding of Syracuse as we know it in the 21st century. Many of the plans put forth and implemented by Grimm—made with good intentions or not—have contributed to phenomena that have created entirely new or exacerbated existing ills within the city. Many of these ills are what planners and policymakers seek a remedy for in the present day. From a close interpretation of these planning artifacts, we can see that Grimm led projects that were consistent with zealous, status quo planning of the 21st century. He can also serve as a symbolic representation of his position and the central role that position plays in the progression of the aforementioned urban trends.

The focus of documents that best detail Grimm’s work in Syracuse come from the 1940’s and 50’s. This is arguably Syracuse’s heyday, as the manufacturing sector was at its peak and the city’s population had surpassed 200,000. With burgeoning automobile use and suburban sprawl being well underway, Grimm and the Syracuse-Onondaga Post-War Planning Council were a principal decision making entity for how Syracuse should address the externalities and effects of these processes. The documents examined here were reports and comprehensive plans either authored or co-authored by Grimm during his time as Executive Director of the Post-War Planning Council. By affixing a curatorial lens on these documents, we can better grasp the state of planning in Syracuse during this period in time.

Traffic (Grimm, 1944a)

The Traffic report, which comes from the volume of the Post-War Planning Council’s Reports of Individual Committees, outlines an abstract plan to improve roadways in the Syracuse metropolitan area as well as how to go about implementing highway systems throughout the city. The plan demands that certain streets be redesigned for the purpose of accommodating higher volumes of automobile traffic and even outlines some possible areas where highways could be integrated into the city. These highways are somewhat different than what would be considered a highway in the present day. As the time this document was authored preceded the implementation of the interstate highway system, many of the called-for highways that are outlined in this plan would resemble multi-lane, wide boulevards rather than massive overpasses for through traffic. The plan opens with a chart displaying the increase in vehicle registrations in Onondaga County over the past 2 decades to the date of the report. This chart shows how total registrations more than triple from 1921 until the time prior to World War II, where they experience a slight decline (1944a). Passenger car registrations, more notably, nearly quadruple during this same time frame.

Streets in various sections of the city are selected for these improvements. In addition, the plan calls for a belt-loop highway around the periphery of the Downtown area. Each of these recommendations is intended to provide “main arteries which serve to collect vehicular traffic from outlying sections of the city

and conduct it to the business center, or to carry traffic from the downtown area for dispersal to other sections” (1944a, p. 53). Some of the streets that were highlighted include Erie Boulevard, West Genesee Street, North and South Salina Street, East Genesee Street, West Onondaga Street, James Street, Teall Avenue and Grant Boulevard. Many of these streets are now known to this day as main thoroughfares in Syracuse. They also encompass all sides of the city and provide the intended arteries from Downtown outwards.

The belt-loop that was intended to encase Downtown would later be realized along West Street, Adams Street and Townsend Street in addition to the later construction of Interstate 81. What was markedly absent from this plan was any mention of the communities where these streets were being designated. The plan lucidly displays the privilege being given to the automobile in the city through the absence and invisibility of the communities in which these roads exist. Wider streets that accommodate more automobiles and faster traffic make other modes of traveling, namely walking, more arduous and hazardous. If one cannot afford a vehicle that can access these roads, then they may be rendered exempt from the future of the city.

Upon many lessons learned from an extensive career in city planning, Grimm authored numerous papers and even a book detailing the practice of urban planning. These writings look at urban planning as a scientific discipline and even compare it to other natural sciences. He refers to planning and how it developed in a way similar to the development of the science of chemistry, stating how chemistry arose out of the pseudo-science of alchemy to take the form of a more useful discipline that it is today (Grimm, 1968). Planning truly is similar in this aspect of the science. The trial and error processes that were once a part of how urban planning was practiced was replaced by a more cogent set of practices that take into account the various dimensions that comprise the urban fabric to ensure that plans are implemented as effectively as they can be. Grimm makes his argument to recognize planning as a science by detailing the various processes and tactics to practice planning. Some of these dimensions include physical planning, environmental planning, land use and zoning as well as private planning (1961). Grimm also stresses the need for community participation in the planning process, and in some of his pieces, outlines how this process should occur. Almost seeming contrary to the approach that he has taken to planning throughout his career, Grimm devotes a chapter in Physical Urban Planning to community involvement and how important it is. This raises the questions of was this aspect of planning present during Grimm’s time on the Post-War Planning Council and if not why would he choose to include it while writing about planning as a science?

Even during his time in office and as Executive Director of the Syracuse-Onondaga Post-War Planning Council, critiques were developed around some of the reports that were published by the council. Found in the Syracuse University Library’s Special Collections on Sergei Grimm, a report authored by Russell VanNest Black takes a critical approach to the planning process in Syracuse and reprimands the reports written by Grimm. This critique cites a lack of specificity in the plans and claims that there is still quite a bit that needs to be done before these plans can be integrated. A quote taken from his take on the previously mentioned Traffic plan states:

“This report, not yet completed, appears to deal rather exclusively and narrowly with highway and traffic matters, tending to glorify the highway above all other community needs. It describes but does not altogether justify the proposed main-thoroughfare system. It represents a part of proposed plan which most needs integration and reconciliation with other parts of the comprehensive picture (1944, p. 11).”

Further, VanNest Black continues to add:

“It will be observed that many of the noted lacks and failures of the individual reports are the natural outcome of the independent thinking of as many special-interest groups and individuals. In preparing the final and consolidated report, it should be possible to fill in the gaps and reconcile the important differences.” (1944, p. 12)

Despite a lack of attention to broader trends that were occurring in city development at the time, this critique helps to shed some light on the authoritative, technocratic nature that was employed by the planning council at the time.

Change in Car Registrations 1921-1943

A chart showing the rapid increase in automobile registrations in Onondaga County

Syracuse-Onondaga Post-War Planning Council- Collection of Reports of individual Committees (Grimm, 1943)

Syracuse Suburban Area (1943)

A map that displays suburban areas that would be suitable for residential development using polycentric rings.

Syracuse-Onondaga Post-War Planning Council- Syracuse University Library Special Collections Center (FHA, 1943)

Land Use in Central Part of City of Syracuse 1900 & 1936

Here are two maps showing the change of land use in Downtown Syracuse from 1900 to 1936—which display an increase in retail uses and parking over time.

Syracuse-Onondaga Post-War Planning Council- Syracuse University Library Special Collections Center (Faigle & Grimm)

James Street Redevelopment Rendering

A drawing depicting the then current state of the James Street corridor with a rendering of possible redevelopment.

Report on the Study of the James Street Area- Syracuse City Planning Commission (Grimm, 1941)

Bibliography

- Devlin, A. (2010). What Americans Build and Why: Chapter 1. Cambridge University Press p. 1-68.

- Ford, L. (1994). Cities and Buildings: Skyscrapers, Skid Rows, and Suburbs: Chapter 4. Johns Hopkins University Press p. 126-185.

- Grimm, S. (1941). Report on the Study of James Street Area. Syracuse City Planning Commission p. 1-40.

- Grimm, S. et al. (1943). Collection of Reports of Individual Committees. Syracuse-Onondaga Post-War Planning Council.

- Jackson, K. (1985). Crabgrass Frontier: The Suburbanization of the United States: Chapter 4. Oxford University Press p. 190-218.

Change in Car Registrations 1921-1943

A chart showing the rapid increase in automobile registrations in Onondaga County

Syracuse-Onondaga Post-War Planning Council- Collection of Reports of individual Committees (Grimm, 1943)

Syracuse Suburban Area (1943)

A map that displays suburban areas that would be suitable for residential development using polycentric rings.

Syracuse-Onondaga Post-War Planning Council- Syracuse University Library Special Collections Center (FHA, 1943)

Land Use in Central Part of City of Syracuse 1900 & 1936

Here are two maps showing the change of land use in Downtown Syracuse from 1900 to 1936—which display an increase in retail uses and parking over time.

Syracuse-Onondaga Post-War Planning Council- Syracuse University Library Special Collections Center (Faigle & Grimm)

James Street Redevelopment Rendering

A drawing depicting the then current state of the James Street corridor with a rendering of possible redevelopment.

Report on the Study of the James Street Area- Syracuse City Planning Commission (Grimm, 1941)

Bibliography

- Devlin, A. (2010). What Americans Build and Why: Chapter 1. Cambridge University Press p. 1-68.

- Ford, L. (1994). Cities and Buildings: Skyscrapers, Skid Rows, and Suburbs: Chapter 4. Johns Hopkins University Press p. 126-185.

- Grimm, S. (1941). Report on the Study of James Street Area. Syracuse City Planning Commission p. 1-40.

- Grimm, S. et al. (1943). Collection of Reports of Individual Committees. Syracuse-Onondaga Post-War Planning Council.

- Jackson, K. (1985). Crabgrass Frontier: The Suburbanization of the United States: Chapter 4. Oxford University Press p. 190-218.