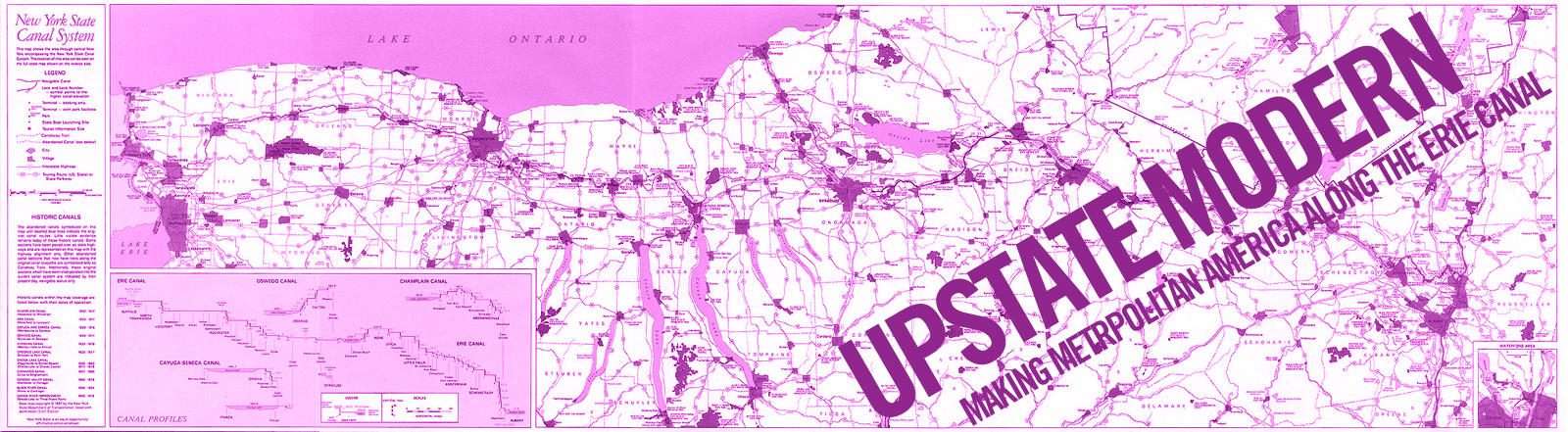

Upstate Modern MAKING METROPOLITAN AMERICA ALONG THE ERIE CANAL

Upstate Modern is a series of courses and public programs at Syracuse University examining the urban history of Upstate New York through transdisciplinary research that draws on archives, buildings, landscapes, and communities.

The 15th Ward: A History in the Shadows

By Leandro Cortez.

Construction of Interstate 81 through Syracuse was the final component in a series of urban renewal projects that eradicated the Jewish and African-American 15th Ward.

The 15th Ward, a name that gained notoriety when Syracuse was divided into distinct neighborhoods for governmental representation. However, by the 1920’s the number of wards had shrunk to 19 board representatives. In 1935 a new city charter destroyed this system of neighborhood representation. Strangely enough the representatives that made the decisions on behalf of the 15th ward did not reflect the Jewish and black majority of the neighborhood. This in a way explains the swiftness with which the policies that were enacted for urban renewal were so little protested at the government level but yet dramatically fought over at the community level.

The city government saw in the 15th ward not only the opportunity to acquire cheap land necessary for the projects but also unrepresented individuals who could not put much of a fight against their urban renewal plans. The lack of information provided to the inhabitants completely excluded them from something that would ultimately affect their lives forever. For the city government of the late 1950’s the 15th ward was to put it simply, a slum. For those who lived within its boundaries, it was home and provided a sense of belonging. For us in the future it is a memory lost. It is a center for culture that never bloomed into what it should have.

The origin of the I-81 project can be traced to the initiatives of the 1960’s with the creation of new government policies that were geared in improving roadway conditions in the form of highways that would better connect expanding cities. Policies such as the 1949 housing act which gave way for “slum” demolition and the 1956 highway act (National Interstate and Defense Act) fueled not only the city of Syracuse’s desire to progress but at a national level encouraged similar programs of “urban renewal”. The 15th ward was chosen as the site of highway because the land in which it stood was quite cheap. Moreover, at the time of construction the predominant African American and immigrant community that inhabited the area did not have representational power in the government and as a result it made it easy to eliminate without much upheaval. As former 15th ward resident Liz Page states in the documentary Our Stories, “People believed the land in the 15th ward was more valuable than the inhabitants of the neighborhood” No one asked the inhabitants of the area what they wanted instead the decisions were made for them.

The proposal for the I-81 highway came in the beginning of the 1950’s. The proposal was part of New York’s master plan to better connect the city with those in the central New York area and with Canada in what was known then as the Penn-Can Highway. The first segment constructed was not in the actual neighborhood but rather within the limits of Brewerton in North Syracuse. After its finalization in 1959 plans for the next stage that would this time slice through the city came into order. It was decided that almond street would serve as the linear outline for what would eventually be the elevated expressway.

Effectively, the I-81 began construction in the late 1950’s until completion in the early 1960’s. The first stage was to evacuate the inhabitants of the first homes that would be torn down. These homes and businesses were stamped on the front door with a “D5 signifying future demolition” while giving the owners time to find a new place. Many times the issue of finding a new home was rather difficult for the displaced African Americans due to issues of segregation and discrimination. As the documentary Our Stories mentions, “When people were relocated from their homes it was difficult to find new places for them to live in since many were subjected to discrimination and as a result negated from obtaining apartments or other forms of housing” As a result public housing projects such as that of pioneer homes were created to house the displaced individuals from the first area torn down, at an affordable price.

What bothered residents the most was the lack of involvement they had in the design and planification of this “urban renewal” project. They never were consulted to see if they were willing to move from their homes and businesses. The methods then for obtaining their property were not made in a way that was clear to the residents and as a result a condition was created were the residents were rapidly being displaced without much time to find residence. The problem was in the legislation that would permit construction because it gave relocation costs and responsibility to the city and not to the companies constructing the highway. Thus the city itself was unprepared for the onset of displacement that would ensue.

Before relocation, residents had to sell their homes the problem was that the price their homes were being forced to sell for was simply not enough for future home ownership. “60 percent of the money would be paid up front and the remainder in monthly payments.” The citizens petitioned the city for adjustment of payment methods which eventually delayed construction plans but when agreements were finalized, the homes in the path of the freeway were set for demolition. The demolition of the first homes occurred on May of 1964 displacing nearly 1,000 people.

The demolition was part of a two phases. The first phase would demolish most of the 15th ward with the exception of a portion towards the southwest part of the sector. The second phase was the restructuring of existing energy, water, and vehicle circulation. During the entire demolition process, no lives were lost. However, the fabric of what used to constitute the only hope for a community was damaged. A community whose integration in terms of race, religion, and even urbanistically through high density living had been destroyed.

Citizens who had escaped the segregation that the rest of the country suddenly faced a new tide, one that would shape the inhabitants for the rest of their lives. The actual demolition of the highway was not immediate in action. After being informed by city officials that their homes were due for evacuation it took nearly two years for the machines to move in and begin the actual process. This was due to the constant change in the design of zones around the highway, circulation routes, and “attachment” projects such as the creation of a plaza for the city and new skyscrapers. The design and construction of the I-81 project was popularly contested among the city of Syracuse. The project’s possibilities ever even known to the Syracuse Architecture students of the time “who proposed realigning the area with a new arterial and displacing more than 250 housing units in the process. The proposal would have created wider streets, a new modern shopping district near the Westcott Street district”

Contrary to the knowledge of the project being carried out by the city stood the lack of knowledge about those who would truly be affected.

https://www.dropbox.com/sh/uv5or35b6qw0h74/ZmJ6j_IXog

Bibliography

- “15th Ward: Memories of a Syracuse Neighborhood Transformed,” last modified April 8, 2013. http://www.digitalicreation.org/gallery/view_galleries/16135/16101

- Kate Stohr, “100 years of Humanitarian Design” (New York, NY : Metropolis Books, c2006.) p. 40-41.

- K. Animashaun Ducre, A Place We Call Home, “ (Syracuse University Press, c2012.) p. 34-35

- Ganle E. Joseph “State Elevation Fear Unfounded,” Herald American, April 27, 1958

- “Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1956: Creating the Interstate System,” National Atlas Gov. Last modified April 8, 2013. http://www.nationalatlas.gov/articles/transportation/a_highway.html

- Black Syracuse, Last modified April 8, 2013. http://blacksyracuse.org/

- Klingel, Nilus, March 16, 2011“ Marcel Breuer in Syracuse”, Infrastructured Blog, accessed 4/21/13

- Our Stories. Directed by South Side Initiative. Syracuse, NY: Daylight Blue Media, 2009. DVD

- Knight, C. Aaron, “ Urban Renewal, the 15th Ward, The Empire Stateway and the City of Syracuse, New York” ( Candidate for B.S Degree in History and Computer Science with Honors Syracuse University 2007)

- Case, Dick. “Memories of 15th Ward ; before I-81, Neighborhood was Syracuse’s “Melting Pot’.” The Post – Standard, Jan 01, 2008, http://search.proquest.com/docview/326369115?accountid=14214 (accessed April 24, 2013).

- Maureen Sieh, Staff writer. “15th Ward Stood Tall, Fell ; 40 Years Ago, a Syracuse Mayor Watched as Urban Renewal Claimed a Neighborhood; Now His Son is Helping Rebuild it.” The Post – Standard, Sep 21, 2003, http://search.proquest.com/docview/325905753?accountid=14214 (accessed April 24, 2013).

- Onondoga Community College, pictures by Mrs. Marie Cloyd & Mr Damon Presley Articles

- Judaic History Center

- Onondaga Historical Association Museum and Research Center, Syracuse, NY

- Aldo Tambellini

- Syracuse Housing Authority

- Special Collections Research Center, The Sergei Grimm Papers, Syracuse University, 4/23/12