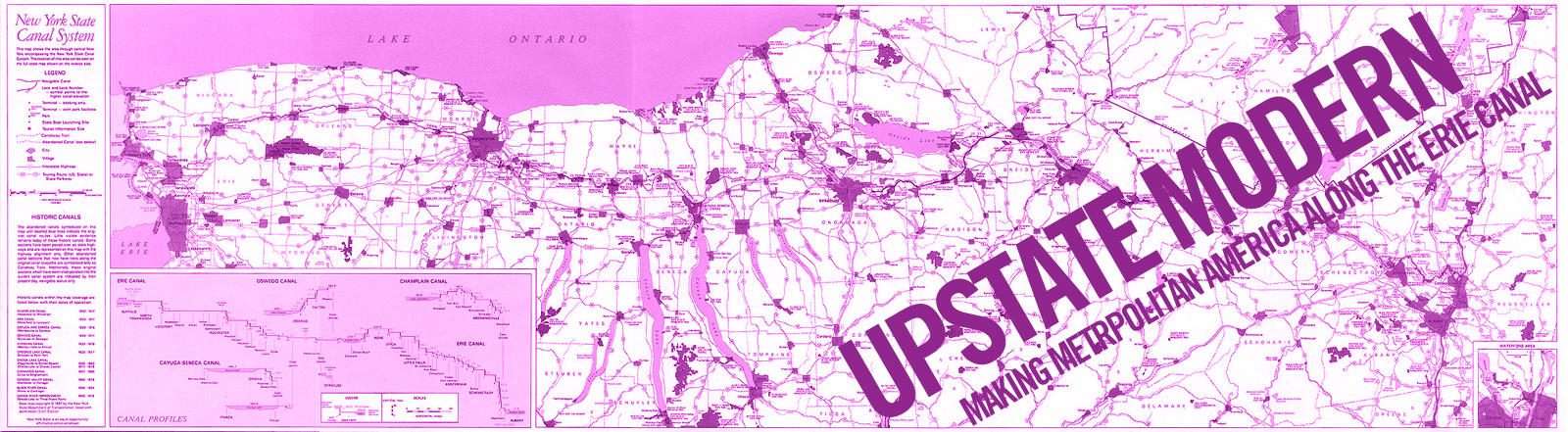

Upstate Modern MAKING METROPOLITAN AMERICA ALONG THE ERIE CANAL

Upstate Modern is a series of courses and public programs at Syracuse University examining the urban history of Upstate New York through transdisciplinary research that draws on archives, buildings, landscapes, and communities.

Cool Kids: The political-economy and pedagogy of school air conditioning

by Derek R. Ford.

South Park High School represents the standard compact air-conditioned school attempting to “increase the educational aspects and decrease the cost of the school building.” In this case, current economic demands dictate the size and shape of the building, whereas in McPherson High School the building responded to anticipated economic demands. For school planning, one of the primary benefits of air-conditioning was the ability to abstract the schoolhouse from its environment. No longer did school architecture need to acknowledge the wind or sun. In fact, windows could be completely removed, as in South Park High. This cut down on initial building costs as well as ongoing maintenance costs. One internal Carrier Corporation memo notes that the absence of windows discourages vandalism. Additionally, air conditioning engineers touted the “improved attentiveness” of children” (McDonald, 1960, p. 78). Again, we see the spillover of efficiency in building materials to efficiency of learning.

Air conditioning technologies and ideologies have their roots not in human comfort but in the production process—thus the term ‘process air conditioning.’ When air conditioning enters the public arena, first through theaters and departments stores and later through train travel, notions of comfort are developed. Yet as air conditioning enters the schoolhouse, beginning in the 1950s, the logic of production tends to dominate. When notions of ‘comfort’ are called upon, they are always in connection to economic efficiency. I argue that air conditioning represents a process of atmospheric reification, and that school atmospheric reification is entangled with the nascent ‘knowledge’ or ‘creative’ economy (Means, 2013), and the attendant post-Fordist organization of capital accumulation.

Process air conditioning embodies capital’s drive to decrease socially-necessary labor-time. Socially-necessary labor-time is what determines the value of a commodity. It is, specifically, “The labour-time socially necessary… to produce an article under the normal conditions of production, and with the average degree of skill and intensity prevalent at the time” (Marx 1867/1967, p. 47). In other words, even if two factories produce commodity x at differing quantities of time, each commodity x produced at both factories would contain the same value. The value of commodity x, however, will not necessarily be constant over time, for socially-necessary labor-time is determined by various circumstances, amongst others, by the average amount of skill of the workmen, the state of science, and the degree of its practical application, the social organisation of production, the extent and capabilities of the means of production, and by physical conditions. (p. 47)

If factory a produces commodity x at a rate above the given socially-necessary labor-time, then commodity x will be sold below its value, and factory a will be forced to either conform to the given socially-necessary labor-time or shut down production. We could certainly add in “air conditions” and “air conditioning technology” as a determining factor in socially-necessary labor-time for hygroscopic industries. This, however, impacts not only economic production but also subjectivity and, as my curation shows, educational theory and practice.

In order to make this link the notion of reification is crucial. In essence, Lukács’ notion of ‘reification’ is essentially Marx’s concept of commodity fetishism—the notion that through the commodity social relations are presented as relations between objects—extended throughout the totality of capitalism. This is so because in advanced capitalism the commodity-form has “penetrate[d] society in all its aspects,” thereby “remould[ing[ it in its own image” (p. 85). This generalization of the commodity-structure throughout society has two implications that are detrimental to society and workers, both of which have to do with standardization, rationalization, the increasing role of exchange-value over and above use-value, and the dominance of abstract labor. First, the object of production itself becomes fragmented in time and space; production processes can be divided up and extended across the entirety of the globe. Second, and most pertinent to uncovering how the individual body becomes standardized by the developmental logic of capital, the subject (worker) of the production process is also fragmented and rationalized; as a result, “human qualities and idiosyncrasies in the worker appear increasingly as mere sources of error when contrasted with these abstract special laws functioning according to rational predictions” (Lukács 1971, p. 89). The working body has to conform to the individual machine and the totality of the capitalist machinery. It is not just that the worker’s movements conform to the movements of machinery. Instead, the workers entire being and sense of self suffer from fragmentation, rationalization, and standardization; “the principle of rational mechanisation and calculability must embrace every aspect of life” (Lukács 1971, p. 91).

Pedagogically speaking, then, education becomes reduced to learning, or the successful transmission of information from A to B—and anything else (e.g., distraction, miscommunication, disruption), becomes a “mere source of error.” Efficiency becomes a pedagogical value and educational processes and practices become tied to demands of global political economy. As these demands begin shifting more and more in the decades following World War II, demands for standardization and efficiency are supplemented with demands for flexibility. School air conditioning technologies, I submit, allow the schoolhouse to do both.

In this image, Barber Colman is attempting to capitalize on recent research into the ideal thermal environment for learning. This research demonstrated that the thermal environment of the classroom should be maintained between 70-75F, and when temperatures rise above or below this range there is an “alertness gap.” Other research, conducted by the University of Iowa in 1962, defined this environment as 70-74F temperature range and 40-60% relative humidity. Implicit within this research and argument is a particular conception of “learning,” in which learning is defined as the successful transmission of information from A to B. This is primarily evidenced in the methodology, in which memory retention was measured between students in controlled environments and students in non-air-conditioned spaces.

This blueprint, designed by Shaver and Company in consultation with Stanford University School Planning Laboratories and administrators, educators, and citizens in McPherson, Kansas, was largely made possible by air conditioning technologies. Having a central air conditioning system was necessary for the creation of large interior spaces. This plan is also a divergence from the compact schools typically associated with modern air conditioning in the 1950s and 1960s. One of the likely reasons for this departure was the high availability and associated lower cost of land. The flexibility allowed for by the plan also embodies the emerging importance of flexibility in pedagogy and political economy, a nod to the nascent post-Fordist ‘knowledge’ or ‘creative’ economy.

This is an image of one part of the academic hexagonal unit inside McPherson High School. The interior of the classroom space can be divided into three separate areas allowing for “station learning.” Additionally, there are moveable partitions between the classrooms of the hexagonal units to allow for multiple types of teaching—individual or the increasingly trendy (at the time) team. The flexibility in classroom design is in response to 1) the projected durability of the school and 2) the re-structuration of the economy to respond to changes in global political economy.

This graphic was developed by G. B. Wadzeck for use as a visual component to a speech delivered at a Symposium on School Heating, Ventilating and Air Conditioning in Pittsburgh on January 29, 1958. The graphic argues that most of the “educational dollar” goes to teacher salaries and, consequently, that increasing teacher “efficiency” will help maximize the educational dollar. He writes, “If we are to stretch the educational dollar, it must be through the better utilization of our professional educators.” One of the methods by which to “secure this mileage… involves the physical comforts necessary for a high degree of efficiency.” Thus, Wadzeck emphasizes the efficiency of the teaching-learning relationship, but basis this efficiency on comfort. This is similar to arguments made for the air conditioning of office buildings.

This advertisement is part of a series linking school air conditioning to the efficient use of the school building. The underlying logic here is that a schoolhouse that is not in maximum use is akin to an idle machine or factory. The schoolhouse is thus viewed as fixed capital and the student is viewed as a commodity (in the previous graphic, the teacher was viewed as labor-power). We also witness an increasing regimentation within education, and can see that air conditioning provides necessary technological requirements for this stratification to occur. Again, the need for “enrichment programs” is tied to the nascent knowledge economy, and most likely also a response to Sputnik.

References

Ackerman, M. (2002). Cool comfort: America’s romance with air-conditioning. Smithsonian Books: Washington, D.C.

Cooper, G. (1998). Air conditioning America: Engineers and the controlled environment, 1900-1960. Baltimore and London: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Jacobs, J. (1961, May). Trial by cooling. Architectural Forum, May, pp. 115-118.

Lukács, Georg. 1971. History and Class Consciousness: Studies in Marxist Dialectics. Translated by Rodney Livingstone. Massachusetts: The MIT Press.

Marx, K. (1967). Capital: A critique of political economy, vol. 1 (S. Moore & E. Aveling, Trans.), New York: International Publishers. (Original work published in 1867).

Marx, K. (1978). Capital: A critique of political economy, vol. 2 (D. Fernbach, Trans.). London: Penguin Books. (Original work published in 1885).

Means, A. (2013). Creativity and the biopolitical commons in secondary and higher education. Policy Futures in Education,11(1), pp. 47-58.

Murphy, M. (2006). Sick building syndrome and the problem of uncertainty: Environmental politics, technoscience, and women workers. Durham and London: Duke University Press.

Ogata, A. F. (2008). Building for learning in postwar American elementary schools. Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians, 67(4), pp. 562-591.

Schultz, E. (2012). Weathermakers to the world: The story of a company, the standard of an industry.

Wadzeck, G. B. (1958). “Educator’s View of Need for Good Classroom Environment.” Pp. 5-9 in School Heating, Ventilating and Air Conditoining. New York: American Society of Heating and Air-Conditioning Engineers.

Zimmerman, J. (2009). Small wonder: The little red schoolhouse in history and memory. New Haven and London: Yale University Press.