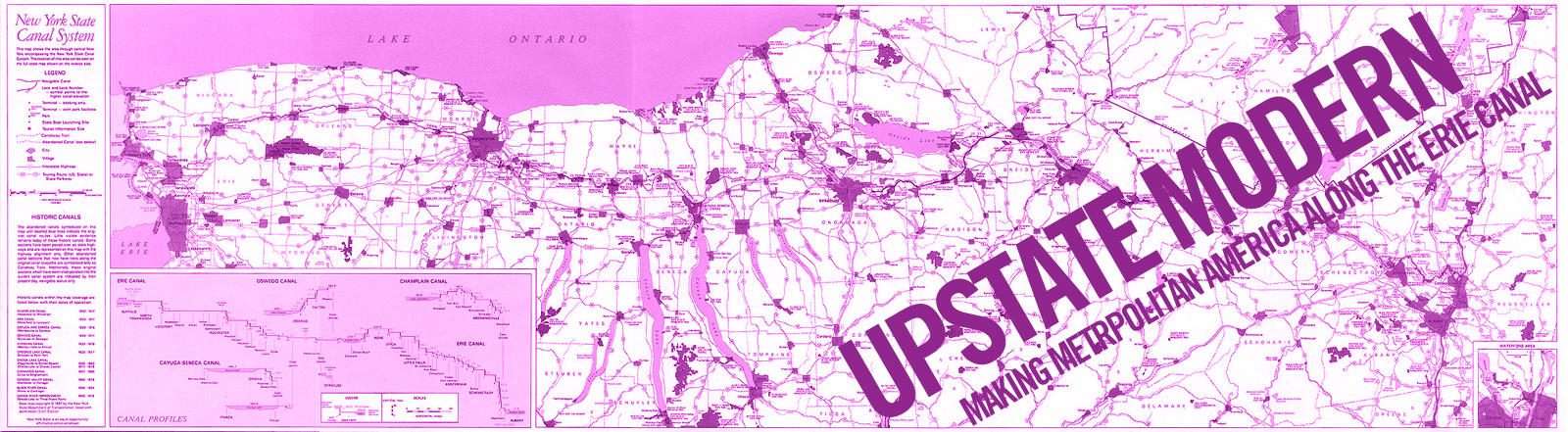

Upstate Modern MAKING METROPOLITAN AMERICA ALONG THE ERIE CANAL

Upstate Modern is a series of courses and public programs at Syracuse University examining the urban history of Upstate New York through transdisciplinary research that draws on archives, buildings, landscapes, and communities.

West Street Severing The West Side

By Nathan Aleskovsky.

How Syracuse city planning perpetuated the economic and urban decline of Syracuse’s Near West Side through the expansion of West Street.

In order to embrace the automobile culture and suburbanization, the 1965 Comprehensive Plan for the City of Syracuse included plans to redevelop areas of the city, which would require the relocation of many residents and businesses. This plan was designed to, “make Central Syracuse the major center of business life and cultural opportunity in Upstate New York. “ In doing so, the mayor and urban planners in the area sought to expand the city both geographically and economically. However, attempting to make “the heart of the city more attractive for working and living” by relocating impoverished residents and creating a beltway around the urban core created an unscalable urban fabric. The proposed urban renewal of the city created and recognized boundaries that limited the city’s ability to expand and promoted economic and racial divisions between neighborhoods.

The severing of the Near West Side neighborhood from the city center is among the most striking examples of this phenomenon. Elevating the rail line and continually widening West Street created a physical and spatial wall between NWS residents and the city center. As transportation technology evolved, jobs along the rail lines in the NWS vanished and residents of the area, were forced to seek work elsewhere in the city, which was difficult because primary pedestrian routes were severed by the raised rail line. By the late 1940’s, most of the wealthier residents left the area and their mansions were replaced by high-density residential buildings.

This series of images shows how the Near Westside Neighborhood slowly becomes disconnected from the overall fabric of the city. In 1938 there is very little disruption in the rhythm of the street grid, however by 2013 there is a clear spatial gap caused by the enlargement of West Street.

CREDIT: 2013. NYS Orthos Online Aerial Photograph of Syracuse, NY. http://www.orthos.dhses.ny.gov/. Edited and modified by the author.

1938. The Cornell Institute for Resource Information

Sciences.

http://aerial-ny.library.cornell.edu/photos/onondaga/1938/ARX-31-94. Edited and modified by the author.

In 1944 the Syracuse–Onondaga County Post-War Planning Council (Planning Council) created a major report that addressed areas around Syracuse in which new interstate highways would be built. This also included intercity highways that would create an arterial “loop” around the downtown area.

“The plan included a ‘belt line’ around the city (providing for a highway without difficult turns or steep grades and allowing traffic to reach the outskirts of the city without having to pass through congested streets), on which through traffic, particularly trucks, could bypass Syracuse if desired; (2) the state thruway, bypassing the city to the north; (3) other east-west thruways in the general direction of Erie Boulevard, a major east-west street formerly the route of the Erie Canal; (4) north-south thruways; (5) a high-speed thruway connecting downtown with the university and medical center; and (6) an alternate plan, a complete loop around the central district” (DiMento 2009, 141).

Figure 1 is a draft proposal from Sergei Grimm as part of the Syracuse–Onondaga County Post-War Planning Council, report, “Postwar Perspective: A Report to the People of the City of Syracuse and the County of Onondaga, 1944”. This map shows the intended locations of the new interstate and intercity primary and secondary roads.

West Street, (connected to South Avenue) appears to have always been considered a choice for an arterial transport. Given its location and directionality in the, it is a logical choice. However, it appears as though the state of New York had far more control over the layout of the interstate system and its connected arteries than many people believe. As specified previously, the map inFigure 1 is a draft proposal. The final proposal regarding exact locations of the roads was not made public.

“Details of the exact location of the arterial through the city have not yet been made public by the State Department of Public Works…. The commission was able only to “presume” where the route would actually run.” (DiMento 2009, 142)

However, by the time this took place, construction had already begun. The City put into action the recommendations of the Planning Council. The West Street corridor was recognized by the City of Syracuse as an area in need of rehabilitation. However, in addition to clearing the blight from the western portion of the city, the City used the project to provide further traffic relief to the downtown area. It appears as though this aspect of the project overshadowed the original purpose, likely due to State involvement. After conducting exhaustive study of the area and preparing their report, the City of Syracuse was essentially removed from the planning process.

“In 1944, legislation had set forth a new policy with respect to city thoroughfares connecting with state highways. Previously, the engineers noted, state highway funds were used almost exclusively in rural districts; the new policy allowed the state to improve and develop arterial routes within the cities themselves, permitting the state to construct “many desperately needed improvements” that formerly could not be built because cities could not finance them. (DiMento 2009, 140)

Additional reports relating to the interstate planning process revealed that the State of New York had far more control over the planning because they were responsible for allocating the necessary funds to the City. It was widely agreed by the City and the State that some type of interstate and intercity highway improvements was necessary for the development of Syracuse (Campbell 1964). However, if the city wanted it to happen, they would have to become submissive to the planning desires of the State (DiMento 2009).

An understanding of the interworking of the construction of Interstate 81 through Syracuse and the City’s growing desire for urban renewal is pivotal to understanding of why and how West Street perpetuated and exacerbated the blight and poverty of the Near West side. As plans were approved by the City and State to use demolish hundreds of homes to create enough space for the elevated highway, plans were also (conveniently) being developed to renew the 15th Ward near City Hall (Syracuse Urban Renewal Agency 1965a). Due to recent federal and state legislation, funds were available to assist the city in removing unwanted blight (DiMento 2009). Thus, during the same period of time, Syracuse was applying for funding for both highway development and urban renewal. In addition, the state still had control over highway planning.

Coincidently, decisions regarding the placement of the highway aligned with areas selected by the city to be demolished as part of urban renewal efforts. Instead of working in a piecemeal fashion as in the past, Sergei Grimm proposed that the city undertake a “comprehensive approach to the city’s housing, slum clearance, renewal, and arterial land-acquisition problems” (DiMento 2009, 148). The resultant plan, which was subsequently approved, destroyed 1,464 living units and took more than 1,200 parcels of

Bibliography

- “1940 Census Enumeration District Maps – New York – Onondaga County – Syracuse – ED 66-1 – ED 66-259.” 2013. 1940 Census Enumeration District Maps – New York – Onondaga County. Department of the Interior. Records of the Bureau of the Census, 1790 – 2007, Record Group 29. National Archives at College Park, MD. Accessed April 1. http://research.archives.gov/description/5835724.

- Blair Associates. 1961. “Population : Trends, Outlook, Implications in the Onondaga-Syracuse Metropolitan Area / Prepared by Blair Associates and the Bureau of Economic Research, LeMoyne College for the New York State Dept. of Commerce and the Onondaga County Regional Planning Board.” Syracuse, NY.

- “City of Syracuse.” 2013. Accessed April 1. http://www.syracuse.ny.us/Census_Tract_Map.aspx.

- County Plan in the Onondaga-Syracuse Metropolitan Area. 1962. Syracuse, New York: Blair and Stein Associates.

- Ducre, K. Animashaun. 2006. “Racialized Spaces and the Emergence of Environmental Injustice.” In Echoes from the Poisoned Well: Global Memories of Environmental Injustice, by Sylvia Hood Washington et al, 109–124. Lanham: Lexington Books.

- Ford, Larry. 1994. Cities and Buildings: Skyscrapers, Skid Rows, and Suburbs. Creating the North American Landscape. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- “Patterns of Land Use in the Onondaga-Syracuse Metropolitan Area / Prepared by Blair Associates.” 1961. Syracuse, New York: Blair Associates.

- Syracuse Urban Renewal Agency. 1965a. “Central Syracuse, The General Neighborhood Renewal Plan, Part 1”. Syracuse, New York. http://syracusethenandnow.org/CompPlan/1965SyrPlan/1965CentralSyracusePlanPolicy.pdf.

- ———. 1965b. “Central Syracuse, The General Neighborhood Renewal Plan, Part 2”. Syracuse, New York. http://syracusethenandnow.org/CompPlan/1965SyrPlan/1965CentralSyracusePlanAction.pdf.